How to Choose a Foreign Language to Learn

How long it takes to learn a foreign language as an adult. Types of motivation, and how to utilise it. Applicability of languages. Planning your study curriculum based on the projected difficulty of a language. The importance of learning about culture. How to improve the effectiveness of your learning process.

0. Introduction

The amount of time you need to reach a basic fluency level in a foreign language (usually considered to be B2 level according to the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages, CEFR) varies drastically and depends on a number of factors, including, of course, individual learning capabilities and ability to focus. There are indicators that to reach it one might need at least about 480 hours of structured instructional setting learning, which to my understanding is overly optimistic: some high-intensity language learning programmes, such as DLIFLC Language School, would demand around 1200 hours and even more in total of classroom-based learning to complete depending on the language, and in a standard graduate university setting second language acquisition programmes are usually taught over the span of 3 or 3.5 years.

Important disclaimer: we are talking about so-called ‘second language acquisition’ — learning a foreign language as an adult or, in some cases, as a teenager. Children under the age of 7 or 8 (in some cases as old as 11 or 12) are still able to acquire the second or even third language as their ‘native’ language, which is a topic for an entirely different discussion.

I will inspect some of the foreign language acquisition programmes as illustrations of certain arguments later, the current point being that although it is clearly achievable to reach a rather high level of command in the foreign language within comparably low and very realistic timeframes, it nevertheless requires careful planning and commitment, therefore making an incorrect choice of a language to learn a costly mistake.

Before delving deeper into the topic I should mention that not everyone embarking on the task of learning a foreign language has a luxury to choose it. Sometimes you should learn a particular language required by your educational institute programme or spoken in a country you found yourself in (as happens in the case of forced immigrationW). To cover such cases I will review some methods you can still utilise to improve the efficiency of your second-language acquisition.

In most cases, however, you are able to choose the language to learn. In academic settings, students are often able to pick one out of several languages that would be beneficial for their line of learning or degree. Those who are inclined to learn a language for professional growth or to improve their career opportunities can pick the language along with the area of research or group of opportunities they would like to pursue. And, obviously, those who decide to learn a foreign language out of curiosity or desire for personal growth are choosing out of the number of options that may be constrained by certain factors, but nevertheless tend to be the biggest compared to the other groups of learners mentioned here.

This article will be beneficial for all of those.

1. Motivation

Motivation is going to be the most important determining factor of your success in learning a new language, as in the case of almost any other skill, acquiring which takes a prolonged period to get enough effective and deliberate practice.

However, motivation is quite an abstract notion, so not only its intensity (or amount) is not possible to calculate with any existing experimental methods, but its classification is also a subject for discussion. Here I will introduce two different classification models of motivation that are (or used to be, as in the case of the first one) highly respected in language teaching and linguistics. As a result, we will be able to better understand the ways of managing our motivation as regards to learning a foreign language and to establish ways of its influence over our choice of language.

1.1. Models of Motivation

1.1.1. Instrumental-Integrative modelThe first model under consideration was introduced by Robert Gardner and Wallace Lambert in 1972 (Gardner, R. C., & Lambert, W. E.). It assumes there are two types of motivation:

→ Instrumental motivation is language learning for immediate or practical goals

→ Integrative motivation is language learning for personal growth and cultural enrichment

It was not possible to determine which type of motivation was connected with better success in learning; furthermore, both intensity and type of motivation are not a stable characteristic of a learner, which is why this model of motivation is considered outdated (Patsy M Lightbown, Nina Spada).

A newer model that we are discussing below is underlining the dynamic nature of motivation and therefore is more reliable to base any co-dependent judgements on. However, the instrumental-integrative model can still provide us with some useful information for the decision-making process.

1.1.2. Process-oriented model

This model of motivation was formulated by Zoltan Dörnyei in 2001. According to this model, there are three phases of motivation:

→ Choice motivation — refers to getting started and setting goals

→ Executive motivation — refers to carrying out the necessary tasks to maintain motivation

→ Motivation retrospection — refers to appraisal of and reaction to your performance

Here is a good example of how this might work:

“A secondary school learner in Poland is excited about an upcoming trip to Spain and decides to take a Spanish course (choice motivation). After a few months of grammar lessons, he becomes frustrated with the course, spots going to classes (executive motivation), and finally decides to drop the course. A week later, a friend tells him about a great Spanish conversation course she is taking, and his ‘choice motivation’ is activated again. He decides to register in the conversation course and in just a few weeks he develops some basic Spanish conversational skills and a feeling of accomplishment. His satisfaction level is so positive (motivation retrospection) that he decides to enrol in a more advanced Spanish course when he returns from his trip to Spain.” (Patsy M Lightbown, Nina Spada)

As you see, this type of motivation model teaches us to think about motivation as a dynamic essence (compare it with the fuel for your car), which can, indeed, depend on internal or external factors, so, instead of concentrating on your choice motivation, you should think about your abilities to manage other types of motivation in future as you progress in your learning of a chosen foreign language.

It should be noted that your motivation over the course of learning a language will fluctuate depending on additional circumstances that would be either difficult to predict or difficult to manage, such as the effectiveness of the teacher or the quality of materials you use for the study. My advice is to still do reasonably detailed research in an attempt to predict whether you would be able to manage these factors to your advantage. We won’t go into the further analysis of your possible models of behaviour since the topic lies outside of our scope of discussion.

1.2. Enjoying the Language

Although not strictly an epistemic factor, you should take into consideration your level of enjoying the language and the culture behind it (or one of the cultures behind it). Do you enjoy the structure, grammar peculiarities, writing system of the language? Do you enjoy the way it sounds? What may appear as negligible at the stage of choosing a language, will grow in importance as you progress in your learning, spending hundreds of hours practising the different aspects of using the language.Additionally, we will talk more about the importance of cultural appeal — for now just take into consideration that this factor will inevitably affect your motivation.

1.3. Practical solutions

When choosing a language to learn, use the Instrumental-Integrative model of motivation to ensure that both types of motivation are going to be present if you start learning a particular language. Thus, to achieve better results, you should have both practical goals for learning a language —understanding how it will help you with certain goals and challenges (e.g. at work, for academic purposes, during travel, for getting more professional opportunities in future), and more general goals connected with your desire to develop personal skills, widen your perspective, and enrich your knowledge about the world.The Process-oriented model of motivation will help you think about future challenges: ask yourself if when learning a particular language you will be able to sustain your level of motivation in the long run with internal and external sources of motivation and encouragement. Opportunities to practise the language, to find qualitative instruction and constant feedback are going to be crucial for sustaining motivation to continue learning a language.

Additionally, do not neglect the simple notion of whether you enjoy speaking the language and using it for other communicative purposes.

2. Applicability

The way you are going to use the foreign language of your choice is, of course, one of the determining factors your motivation is built upon. However, it should be studied additionally since your initial plan of how and where you are going to be using the language might be subject to significant changes over time: your motivation to use the language for a particular professional opportunity might be significantly weakened by a sudden career change, and your eagerness to learn a language out of desire to learn more about a certain culture can suffer with the rearrange of your personal growth plans.

Although I do not think that any time spent learning a new foreign language is time lost if you suddenly deprioritise it, it would still be wise to pick a language that is so well aligned with the current demand that the chance it would be useful and engaging for you stays very high no matter what.

Thus we speak about the target language’s applicability.

Here, by ‘applicability’ we understand the demand for using/knowing a particular language in a number of different situations and areas of life. Applicability of a certain language can be either general or individual.

2.1. General Applicability

The general applicability of a language indicates its general demand in the whole sum of instances where it can or should be used, to speak more simply — how ‘popular’ is the language.

I instantly think of two types of determining the target language’s general applicability.

2.1.1. Number of speakers

Firstly, we can assess what part of the world’s population is speaking a target language — it will grant us some understanding of how frequently the opportunities to use the target language might occur. For our purposes, I would suggest using the total number of speakers, and not just the number of native speakers. Compare the two following tables (source: one and two):

The first is top-10 languagesw by population of native speakers.

The second is top-10 languagesw by total number of speakers.

Just by looking at the position of the English language in the first table that provides us the number of native speakers, it becomes clear that this approach presents to us very limited and skewed data for making a decision: Spanish and Mandarin are put before English in popularity, although it is obvious that English can be used much more frequently all over the world in general.

Therefore, the second table, which indicates the number of all speakers of the target language, gives us a much more adequate and all-round picture of how popular is the language, according to which English is the first, Mandarin is the second, and Hindi — not Spanish — is the third in this hierarchy. Again, these numbers provide you with a very generalised view, but they are able to give you some understanding of the language’s spread and usability.

2.1.2. Areas of Use

The second approach would be learning which languages have high-ranking official statuses in the most powerful world organisations or areas of activities, which can, again, to some degree indicate the language’s relevancy and if it is in demand in the areas you are interested in.

For example, there are 6 official languages used by the UN: these are Arabic, Chinese, English, French, Russian and Spanish. It is a strong and valid assumption that if you need a language well connected and used in the world of global politics and economy — you can definitely pick one of these six languages.

We should also look at our specific areas of personal and professional interest to see if learning a specific language will give us some form of advantage there.

Here is a very illustrative example: currently, the universal language of science is indisputably English, with more than 85% (and in some cases more than 95%) of scientific publications written in English. Therefore, even though Mandarin is not too far behind English in the total number of speakers, and even is significantly ahead of it judging by the number of native speakers, its applicability in the scientific world cannot even closely compare to the one of English language.

However, one can have their individual set of circumstances that would influence the language’s applicability: if you live on the border with China, planning to study the history of the Qing dynasty at the Peking University, and most of your friends and family are already living in China — you might look at the situation quite differently.

Thus we also talk about the applicability of language as seen from your personal perspective.

2.2. Individual Applicability

As you might have already realised, the general applicability of the language might not be very well aligned with your personal demand — therefore, we can also speak about language’s individual applicability.

Consider the following questions:

- Which languages are spoken in the country of your residency?

- Which languages are spoken in the neighbouring countries?

- Which languages are spoken by the members of your family?

- Which languages are primarily used in your area of professional, cultural, or personal interest?

Giving yourself time for diligent exploration of these questions will help you ensure that you pick a language which would be useful for you in the most amount of possible scenarios.

From my personal point of view, a particular language’s individual applicability is one of the first and most important factors to evaluate when deciding which foreign language to study.

3. Language Difficulty Rankings

While not the most important argument for or against choosing a particular foreign language, its relative difficulty can be a good way to calculate the effort it would take you to reach the desired level of fluency within a certain timeframe.

The key word here is relativity. It is not possible to calculate neither the exact amount of effort nor time you’ll need to spend to master the language to a certain level (there are simply too many variables), but we can still approximately predict the difficulty level of one particular language or language group relative to another.

To assess a particular language difficulty you should take into account the following parameters that are going to be different for everyone:

- The language family of your native language and of the target language. It is easier to learn a new language that is related to the one which is either your native or the one you are already fluent in. For example, it is generally easier for Swedish speakers to learn English, than it is for Chinese Mandarin speakers. Also, it would be easier for the Chinese Mandarin native to learn French after becoming fluent in English, as compared to learning French as the first foreign language.

- Pattern recognition skills. To quickly master basic and to correctly use advanced grammar one needs good pattern recognition skills, so if this is your weak spot — you will be struggling more with languages with complex grammar structure. At the other hand, it won’t be a huge problem for you if learning an analytic language, for example, one that utilise Chinese characters in its writing system.

- Memory skills. A similar approach can be used here — the languages that require a lot of memorisation of either writing symbols (such as Chinese Mandarin) or grammar categories even at the basic level would be quite difficult for you if your visual memory is not your strong side. At the same time, your audio memory will be crucial to mastering speaking tonal languages.

It may seem confusing, especially for a person with no linguistic background or no previous experience of learning languages, so you may conduct your research first.

To find a place to start such a research, especially if you are an English language native or are fluent in English, you can check the language difficulty ranking by the DLIFLC Language Institute:

Category I&II languages — 36 week-long courses:

- French

- Spanish

- Indonesian

Category III languages — 48 week-long courses:

- Persian Farsi

- Russian

- Tagalog

Category IV languages — 64 week-long courses:

- Modern Standard Arabic

- Arabic — Egyptian

- Arabic — Iraqi

- Arabic — Levantine Syrian

- Chinese Mandarin

- Japanese

- Korean

As we see, the Institute has 13 language intensive courses with languages (and language dialects) sorted into three categories according to their difficulty. According to this classification, French, Spanish, and Indonesian languages are the easiest to master for English speakers. Indonesian here is Category II since it is rather different from languages of Romanic or Germnanic group, but still very manageable for the English speakers. Russian falls into the third category with 50% longer period of study — cyryllic alphabet and its complex syntheticw nature makes it quite hard for those who were not exposed to it or other Slavic languages before. Arabic and Chinese-alphabet languages, which utilise a completely different logics and writing systems, are even harder and demand almost twice time as the languages from the first two categories.

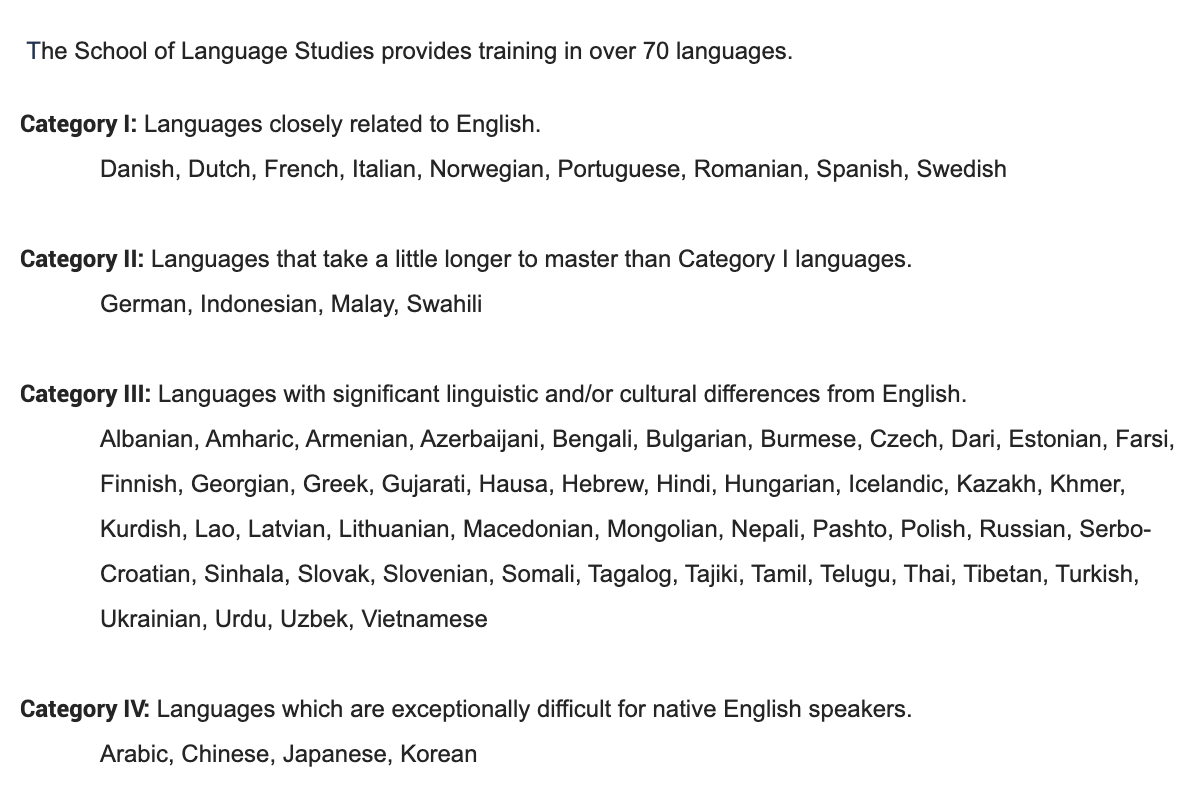

There is a similar, but slightly more detailed difficulty classification from the School of Language Studies at the Foreign Service Institute, that can be found here.

Again, such classification will not provide you with the exact number of classroom instruction and practice hours you need to master a language. However, these difficulty rankings, being very approximate, can still be a great illustration even if you are not a fluent English speaker — just use the same logic in approaching the determining factors that will influence your aptitude for a particular language, taking into account the points mentioned at the beginning of this chapter.

4. Culture

You won’t be able to make significant progress in learning a foreign language and achieve fluency in it unless you understand the culture behind the language you are aiming to master. There are numerous research on the importance of learning languages along with lessons on the history and culture of the people/countries/nations using that language, but to keep this material purely practical let us just mention the most obvious reasons for that (if interested, you can start with the book by Ildikó Lázár, see References at the end of this articles for details).

The study of culture behind the target language allows students to:

- Develop communicative competence for use in situations the learners might expect to encounter

- Understand and use implicating and indirect language: humour, irony, cultural references, etc.

- Improve knowledge of the etymology of language

- Have significantly higher motivation to learn and practice the language

- Widen opportunities to use the language

- Develop awareness of the target language

Now that you understand the importance of learning about culture along with studying the language, you have to see if it appeals to you and if you are as interested in learning the history of the language and of the people who speak it. Your strong appeal or dislike towards a certain culture should be one of the decisive factors in your decision to either learn or not learn a particular language.

5. When you don’t have a choice

As it was mentioned at the beginning of this article, it is not always the case that you can choose which foreign language to learn — there can be a practical necessity to communicate in a certain language that makes you learn it. Often — as quickly as possible.

For such cases, the following advice will help you to be more precise and effective with your learning process:

- Back to talking about culture — start with extensive research of the target language’s history and the culture behind it. If you learn the language of a country you relocated to, also learn this country’s history. There is a reason behind the existence of history exams during the naturalisation process for immigrants. This will boost your motivation to learn a language and provide you with numerous new opportunities to practice it and help you to find more common ground with the people speaking that language.

- Spend your free time immersed in the activities encouraging you to study and use the language — be it social activities, such as joining a study group or visiting lectures, or personal, such as reading books or listening to podcasts in the target language. These activities should be meaningful for you so they don’t feel like part of a learning routine, but something you would do in your native language nevertheless.

- Become an avid networker. Socialising in a target language will not only provide you with more practice ground to polish your communication skills but also just feels good every time you speak a foreign language and you are understood. Thus you are making communication achievements and as a result your motivation will be improved and you will be encouraged to work harder for achieving even better results.

As a secondary benefit active networking in a target language is going to help you assimilate into a new culture faster, if that is your purpose.

6. In conclusion

When you read stories about polyglots or just people who learned a foreign language fast, achieving impressive results, you will see that there is always a practical necessity or reason behind learning a language, which is why when we speak about choosing a language to learn your motivation should be the first factor for consideration.

The next step would be assessing the applicability of languages you are choosing from. Do not forget that it is going to vary for each individual depending on their specific set of circumstances.

It will be useful to also take into account the target language’s difficulty — once again, it will vary depending on your background. Do not forget, though, that this is more of a planning factor, rather than decisive — if you put in the required amount of effort, you will be able to learn any language, no matter what your language and/or learning background is.

Do not forget about the utter importance of learning about history and culture that stands behind the language — it will help you master the language to a much higher level and significantly improve the effectiveness of your learning process.

In conclusion, it should be emphasised that even if you have to learn a specific language due to the set of circumstances you find yourself in, you can still drastically improve your chances of mastering it effectively by utilising effective approach to your study of the language and the culture behind it.

Additional References

- Gardner, R. C., & Lambert, W. E. (1972). Attitudes and Motivation in Second Language Learning. Rowley, MA: Newbury House Publishers.

- Ildikó Lázár, 2003. Incorporating Intercultural Communicative Competence in Language Teaching Education. Council of Europe Publishing.

- Patsy M Lightbown, Nina Spada, 2021. How Languages Are Learned, 5th Edition. Oxford University Press