Everest death zone as a metaphor, and why you shouldn’t go there alone

Death Zone of mount Everest — one of the deadliest places on Earth. How many people are ending (up) there. The notorious case of David Sharp. Not so obvious implications with examples from the 6-years old version of the same essay.

The first version of this essay was written some six years ago, and it was my very first essay in English outside of school environment, written as a way to reflect on certain life — I wouldn’t say events, rather — experiences. I was in search of a good metaphorical image, and (I don’t remember how exactly) I stumbled upon a story of David Sharp, but, more importantly — the description of Everest’s ‘death zone’ and the stories of all those who have ever stepped inside it. Now when I decided to update the essay, I realised that since that time Everest took its toll with many others, sometimes in an even more dreadful way than described here — recent years were not kind to a lot of those who tried to conquer the highest peak on Earth. However, I am going to tell the original story — it is still closely connected with the conclusions I came to at that time, and I still consider that story to employ more illustrative power than the events that took place later.

The peak of Mount Everest is 8848 metres, making it the highest peak on Earth. The only reason it hasn’t turned into a crowded tourist attraction is difficulty of getting there. However, one may argue about it: as of June 2020, 5780 different people reached the summit of Mount Everest — notice that this statistics does not include those who climbed it several times.1 Each year approximately 800 people attempt to climb it during the short spring period.2 More than 300 of them died, most of the times — in the ‘death zone’.

Death zonew starts at 8,000 metres and is called so because the amount of oxygen in the atmosphere at this altitude is insufficient to sustain human life for even a relatively short period of time. No matter how hard you train and prepare, you can’t acclimatise. In brief, our bodies are functioning best at sea level with the atmospheric pressure equalling to 101,325 Pa or 1013.25 millibars = 1 atm, where the concentration of oxygen in air is about 20.9%. In these conditions we receive enough oxygen to saturate hemoglobin, produced in red blood cells, which then take up oxygen to the lungs. At 5000 metres the atmospheric pressure is lower, and the concentration of oxygen is at about 50% of its sea level value, or, we may call it, ‘healthy level’ value. The mount Everest base camp is situated exactlly at that altitude, and those who would like to climb the summit have to first spend weeks in the camp to undergo a process of altitude acclimatizationw. During this period the heart rate increases, non-essential body functions are suppressed, breathing becomes more frequent and deep, and the additional red blood cells are produced. Such procedure lowers, but still leaves significant risk of getting attitude sicknessw —negative health effects caused by exposure to low amounts of oxygen, such as tiredness, trouble sleeping, hallucinations, and others, that can lead to potentially deadly high altitude pulmonary edemaw or cerebral edemaw. Even experienced mountaneers when staying at altitudes higher than 1500 metres are risking to get such health conditions, and the higher the altitude, the higher the risk. Those who climb extreme altitudes (5.5 km and more) can bever predict how well their body is going to acclimatize, and how it will behave, and especially so in the death zone, where the concentration of oxygen is only at about third of a norm.

By the way, just for your reference, do not mix up a term ‘death zone’, which we are talking about, with ‘dead zone’ — these are very similar in spelling, but different terms. Dead zones are also areas with a reduced level of oxygen, but in water. Very few organisms can survive in those areas appearing in sea and fresh waters due to a set of different reasons. If you would like to know more about it, you can start with reading this material from National Geographic.

But let us return to Everest. The way to the summit located inside its death zone is kilometers long, and the ascention is extremely dangerous. Even if you use supplemental oxygen, your muscles are going to be severely weakened, and you will have to hurry in order to minimise the time you spend there. Typically, mountaneers leave 8 km camp at 2 in the morning, rush to the summit, spend several minutes there, breathing the thinnest air on the Earth, and then quickly descend back to the camp. The more time one spends on such altitude, the more chances he has to stay there forever, and death on Everest can be both mysterious and casual at the same time: right now there are hundreds dead bodies scattered across the mountain (bodies are very expensive to transport from the top, so most often they are left at the trail or in the camp and are used as landmarks), which made one of mountaneers recently describe going to the summit as ‘walking over bodies’.3

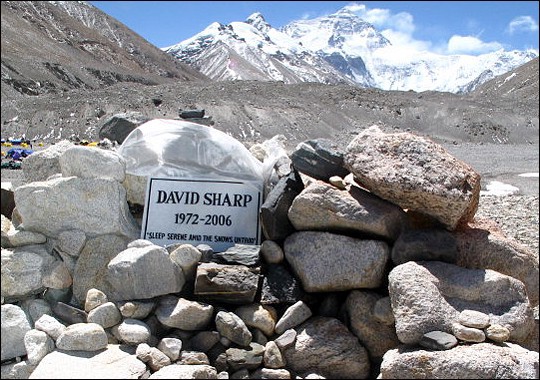

One of such landmarks, situated in the death zone, is the ‘old green boots’ — a cave with a perfectly preserved corpse wearing green boots inside. In May 2006 several groups of more than 30 mountaneers in total approached ‘green boots’ on their way to the summit. Some of them saw another man sitting inside the cave right next to the ‘green boots’. His name was David Sharp, but they didn’t know him, and they were not sure how he happened to be there. It seemed he was on his way back from the summit, but didn’t make it before dark and stayed in the cave for a night. The man didn’t have oxygen with him, was not moving and was hardly breathing. Some of the climbers were not even sure he was still alive, but the main question was: why was he alone?

***

I have stumbled upon the case, or the story, if you like, of David Sharp, in 2014: that was a curious period of my life, one of the happiest, actually, because I met a lot of new people, some of whom became my good friends, and learned a lot from those encounters. But sometimes I would get frustrated and even angry with people I met: they didn’t understand me, I didn’t thoroughly enjoyed their company, and it seemed easier to not put any efforts into making things right between us. I was a very young ambitious man, and still enjoyed the idea of going through life on my own, without need of any assistance from others. ***

Later in the day the group of mountaneers passed by ‘green boots’ cave on their way back. David Sharp was still there: now, in the daylight, they could see he was still alive. However, in the death zone, rescuing a person is so much more difficult than in normal conditions: every member of the expedition to the summit was exhausted, their muscles were weakened by the laxity of oxygen, and it would take twenty fresh people to carry one person to the camp. “I realised that, well, we don’t know who he is, he certainly looked more dead than alive, and my primarily responsibility is to the clients and the people who were with me”, were the words of one of the mountaneers who saw David Sharp that day.4 The only hope for David Sharp was to stand up and walk on his own, supported by several other experienced climbers. They tried to help: they moved him in the sun, and he was able to tell them his name. Then they helped him to his feet, and he was able to make four small steps in 25 minutes. Even the strongest climbers capitulated and admitted they couldn’t do anything. They helped David back in the cave; some of the people walking by him looked at him; some of them tried not to look; one got to his knees and read a prayer.

“That’s why you don’t climb alone, so that those around you can address the issues before it’s too late”, said Mark Ingalls, who was part of a group that left David Sharp to die. David went to the summit alone, he didn’t have radio that he could use to ask for help, when he realised he was too exhausted to move, he didn’t have supplementary oxygen that could temporarily sustain him and give him additional time to leave the death zone. It is assumed that before staying in the cave next to the ‘old green boots’ he was able to reach the summit; he was no doubt strong, experienced and skilled mountaneer, and he made one of the toughest climbs in the world. He reached the highest peak on Earth, without help, all on his own. He could be proud of himself.

On the way back he died, alone, and there was no one to help him or to stay with him at the moment of his last breath.

Additional references

- “Full List of Mount Everest Climbers”

- “14 Fast Facts about Mount Everest”

- ‘Walking over bodies’: mountaineers describe carnage on Everest

- ‘Dying for Everest’ documentary on Youtube